By Darlene McCormick Sanchez

In arid South Texas, home to mesquite and cacti, it hasn’t been uncommon for commercial beekeeper Robert Wheeler to lose half his bees every year.

But this year has been far worse.

His family-owned Frio Country Farms lost 2,000 of its 3,000 bee hives this year, many of which would have been pollinating crops such as watermelon and almonds had they lived.

And he is not alone. America’s bees are dying at an alarming rate as scientists try to figure out why.

The main suspect is the deadly Varroa mite, a vampiric parasite that carries viruses and has become immune to Amitraz, the primary pesticide used to kill it.

Wheeler, a commercial beekeeper since 2019, said he is one of many in his trade who relied on Amitraz to keep his colonies healthy.

“Some big beekeepers are hurting pretty bad right now because it takes a lot of money to run a big bee operation, and you can’t have a mistake because it’ll cost too much,” Wheeler told The Epoch Times.

“It is a pretty big deal what’s going on,” he said. “I mean, everything we eat is pollinated.”

Bee Crisis

Viruses spread by the Varroa mite, a devastating parasite that pierces the bodies of bees to drink their blood and nutrients, are the chief suspects, according to a U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) press release issued in June.

Scientists examined mites from collapsed colonies across western states in February and discovered signs of resistance to Amitraz, a critical miticide widely used by beekeepers.

“This miticide resistance was found in virtually all collected Varroa, underscoring the need for new parasitic treatment strategies,” according to the agency.

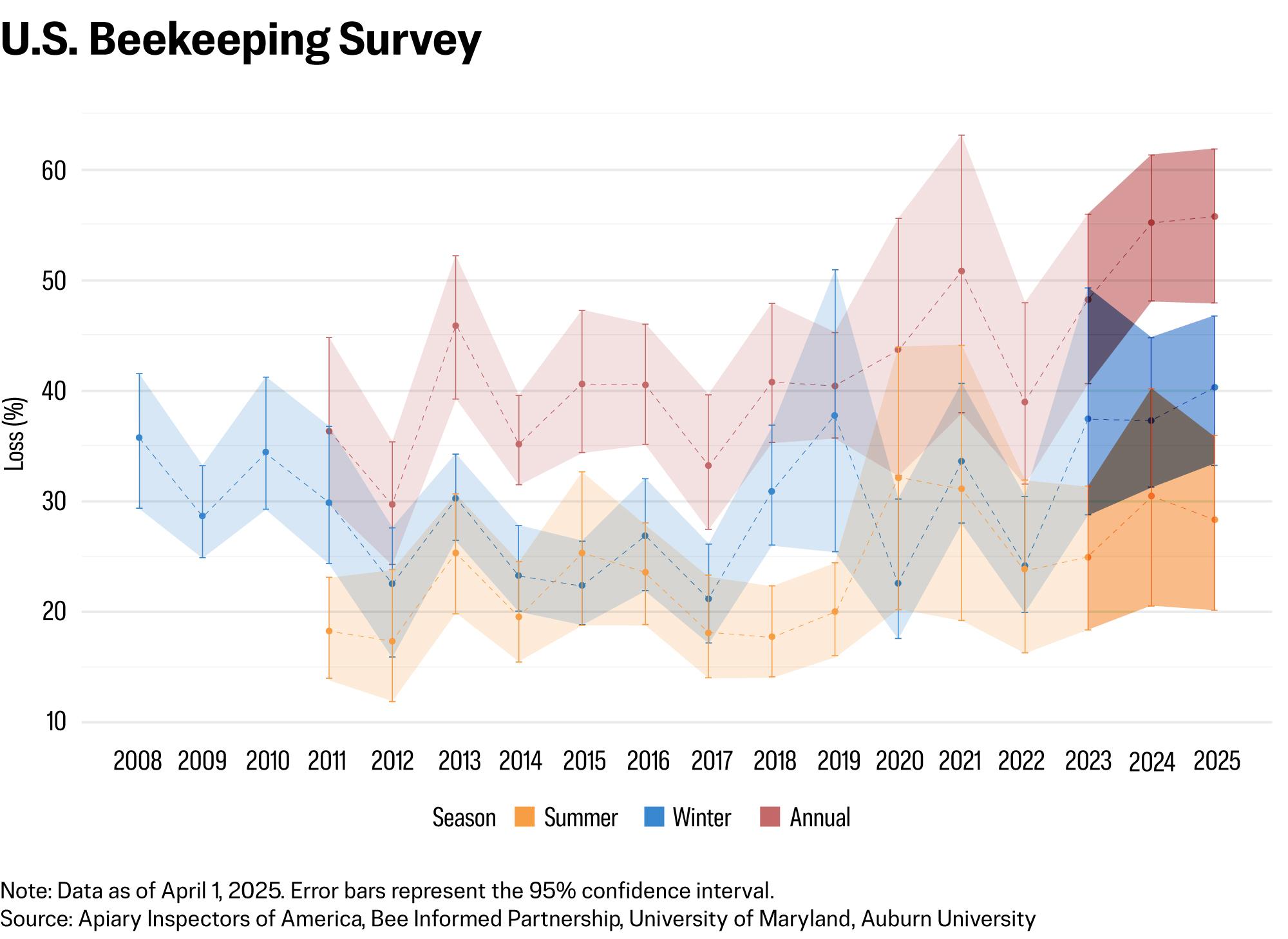

The agency stated commercial beekeepers lost 1.7 million colonies, amounting to more than a 60 percent loss from summer 2024 through January. The economic impact was estimated at $600 million.

Some beekeepers reported 80 percent or more hive losses, according to bee surveys.

A survey carried out by the Apiary Inspectors of America noted “staggering” colony losses of more than 55 percent in a 12-month period ending April 1.

The survey report said the losses were the highest reported since the annual survey first began tracking them in 2010–2011.

“Experts warn that without immediate intervention, the ripple effects could drive up costs for farmers, disrupt food production, and shutter many commercial beekeeping operations,” according to a joint press release from the Honey Bee Health Coalition, released this spring in reaction to the losses.

“In January 2025, beekeepers across the country began reporting unexpected large-scale honey bee losses—we now know the largest ever recorded in the U.S.,” Danielle Downey, executive director of Project Apis m., stated in the same release.

The center holds the country’s bee lab, a frontline research facility studying Varroa mites.

The Epoch Times did not receive a response from the USDA concerning the details of how the relocation might affect bee research.

Impact on Beekeepers

In Texas, beekeeping has undergone a renaissance thanks to a 2012 law that grants property tax breaks to landowners who keep bees on at least five acres.

A conservative estimate puts the number of Texas beekeepers at 6,000, including backyard beekeepers, “sideliners,” or medium-sized beekeepers with small businesses, and commercial bee operators.

In the state, however, the average loss stands at 61 percent over the past year, according to preliminary survey results from the Apiary Inspectors of America.

That rate has typically been more than 40 percent in recent years, far above the expected loss of about 25 percent, according to Garett Slater, an entomologist researching bees at the Texas A&M AgriLife Research and Extension Center at Overton, Texas.

“They’re relying on Amitraz, and it’s not working,” Slater told The Epoch Times. “Their mite levels are exploding.”

The consequences could be far-reaching since crops such as carrots, onions, blueberries, apples, cucumbers, melons, and almonds depend on bees for pollination.

Slater said about a third of food crops rely on bees for pollination.

“If you ever go to your grocery store … those shelves would look pretty bare if we can’t have bees for pollination,” Slater said.

Commercial beekeepers—generally those with more than 300 colonies—have been hit particularly hard, making it difficult to provide bees for California almond crops, where operators can make $250 per hive.

About 80 percent of the world’s almonds are produced in California, which require 80 billion insects, or 1.7 million hives, for pollination.

“These losses are more widespread than ever before,” Slater said. “They’re experiencing probably the highest loss we’ve ever received for the commercial beekeepers.”

Researchers are just now getting the data they need to assess the impact on almond pollination, he said.

Some beekeepers may be unable to stay in business if they sustain high bee losses year after year, though many split their hives to rebuild numbers.

“But 80 percent losses—it’s really hard to take that 20 percent to make up for that 80 percent loss,” Slater said.

Slater’s job, which was created at the university last year, will support beekeepers and promote good practices across the state.

He is also starting Texas’s first bee breeding center—one of a handful in the country, he told The Epoch Times.

The goal is to breed queens that produce bees that destroy Varroa mites within a colony.

However, nationwide bee losses can’t be entirely explained by the unchecked spread of pesticide-resistant Varroa mites. Some believe pesticides and herbicides weaken the bees, along with poor nutrition, making them more susceptible to viruses.

Corneliu Prelipceanu, a commercial beekeeper in California’s Bay Area, does not use Amitraz, and still suffered high losses. He uses organic pesticides such as formic acid and oxalic acid to kill the mites.

Prelipceanu experienced his worst year since 2010, when he started his company, Elsi Bees.

This past year, he lost 50 percent of his hives, significantly higher than the normal 20 to 30 percent loss, he said.

Blood-thirsty Mites

Of all the threats that bees face, the Varroa mite has proven to be one of the most lethal since arriving in the United States in 1987.

They feed on the body fat and blood of bees, and also spread the deadly deformed wing virus, according to a study published by the National Institutes of Health.

“Mites are basically like having a plate-sized parasite on your chest if you’re a bee,” Slater said.

Beekeepers began using insecticides such as coumaphos to kill the mites, but they became immune to the treatments around 2005, he said.

They eventually switched to the insecticide Amitraz to kill the mites, which they’ve continued to use over the past 20 years. It’s a popular, widely used insecticide used in agriculture and veterinary medicine to control fleas and ticks.

While there are alternatives to Amitraz, they pose problems for some beekeepers.

Beekeepers can use organic pesticides such as oxalic acid, formic acid, and thymol, Slater said. But it can be a problem in warm southern states because formic acid and thymol can’t be used once the temperature rises above 85 degrees Fahrenheit.

As for oxalic acid, it won’t kill the mites that hatch inside the cells where they begin to feed on bee larvae and pupae.

Sublethal Pesticides

Slater said the mites are part of the five Ps driving high bee mortality rates: Parasites, pathogens, pesticides, poor nutrition, and poor management.

Pesticides have long been suspected as a leading cause of bee colony loss.

Marin Tomulet and his wife, Rodica, run Joyful Bee Farms in Quinlan, Texas, usually keeping between 100 and 150 hives.

Tomulet said that farmers sometimes contract with third-party pesticide providers that spray crops, unaware that bees are in the fields.

It also costs the farmers money if they have to pay beekeepers to load their bees on a tractor-trailer to temporarily relocate their hives away from the fields being treated.

Wheeler, whose bees pollinate watermelon crops, said he has run into problems with at least one farmer spraying their fields with fungicides, which makes the bees sick.

“The people that are raising watermelons, some of them are good farmers and good people that care about the bees, and some of them aren’t,” Wheeler said.

That has led Wheeler to ask farmers to spray insecticides or fungicides at night, or when the bees aren’t active. He is also spending thousands of dollars on feeding the bees probiotics to help their digestive systems recover from the fungicides.

“The most toxic thing for a honeybee is wet chemicals,” Wheeler said.

A class of pesticides called neonicotinoids has been closely scrutinized since honey bee deaths garnered global attention 15 years ago.

“Vanishing of the Bees,” a documentary released in Great Britain in 2009, suggested there was evidence linking neonicotinoids to Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD), a phenomenon in which most of the worker bees in a honeybee colony suddenly disappear, leaving behind the queen, food, and a few nurse bees to care for the remaining immature bees.

A 2015 review of CCD concluded that “a strong argument can be made that it is the interaction among parasites, pesticides, and diet that lies at the heart of current bee health problems.”

Less than lethal amounts of neonicotinoids were thought to build up in the bees’ system, compromising their immune system, navigation, and memory.

Neonicotinoids, used to coat some crop seeds, remain in the plants throughout their lifespan and can be expressed in pollen. They are even used to coat some crop seeds.

Although this family of pesticides has been banned in European countries, it continues to be used in the United States, though it’s under review by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Legislatures in Washington state, California, Colorado, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont have enacted laws restricting neonicotinoid pesticide use.

Help from science may be on the horizon as well. A 2024 study found that feeding bees hydrogel microparticles helped them recover from neonicotinoid poisoning.

Slater said farmers are often faced with difficult decisions when it comes to using pesticides to protect their crops.

“If you don’t use neonicotinoids, then you might have to use something else that could be more toxic,” he said.

Breeding Better Bees

Deep in East Texas, on a two-lane blacktop road past tall pines and hardwoods, sits Texas A&M University’s first bee breeding facility that is part of its new extension service for beekeepers.

The old facility, once used for horticulture, will be repurposed to breed bees capable of battling the Varroa mite.

By selecting queens from hives with natural mite-fighting behaviors, scientists can produce bees that are more “hygienic,” meaning they are more aggressive at removing diseased or damaged broods from the hive.

At the bee lab, technicians will extract bee semen and then inseminate the queen beginning this August. After breeding for mite-biting traits and the ability to remove mites from within the cells of baby bees, Slater hopes to distribute queens to beekeepers in Texas.

The goal is to create a co-op where beekeepers share in the expenses and receive mite-resistant queens in exchange.

Bees belonging to Marin and Rodica Tomulet make honey in Dickinson, N.D., on July 27, 2025. Some 2 million bees are in the Tomulet hives. Samira Bouaou/The Epoch Times

Breeding bees for specific behaviors isn’t new.

Daniel Weaver, a fourth-generation Texas beekeeper, told The Epoch Times he has spent decades breeding bees resistant to Varroa mite and viruses.

Weaver runs the BeeWeaver Honey Farm in Navasota, Texas, started in 1888, and also sells specially bred queens.

The family got into the business of selling queens produced in conjunction with a monk at Buckfast Abbey in England, who developed a line of queens resistant to Acarapis woodi, also known as honeybee tracheal mites.

Tracheal mites were a severe problem for honeybees in the United States in the 1970s and ’80s, Weaver said.

In 1992, Weaver told his father that he wasn’t about to spend his entire life putting insecticides into the bee colonies.

“We’re going to have to figure out a different solution to this problem, and Varroa mites were very, very much a problem,” Weaver recalled saying.

“So I thought, why not try to do the same thing with Varroa?”

Respected entomologists and bee scientists called him “crazy,” saying it wouldn’t work.

“One of them famously said trying to breed bees that are resistant to Varroa mites is like trying to breed sheep that are resistant to wolves,” Weaver said.

Weaver did it anyway, breeding queens from hives that survived Varroa mites without treatment.

“In my experience, it takes a combination of many different traits to create a bee that’s really going to be highly resistant to Varroa mites,” he said.

Since the crisis struck the honey bee industry this past year, his phone hasn’t stopped ringing.

“I’ve gotten more orders [for queens] than I can fill,” he said.

Love and Honey

The Tomulets moved to the United States in the 1980s from Romania, where it was common for families to keep bees and produce their own honey.

Their love of bees has helped them remain successful.

In late July, the couple drove from Texas to North Dakota, known for being the nation’s top honey-producing state, to harvest honey.

Many of their Texas hives spend the summer in North Dakota, a haven for bees with its lush rolling farmland, once home to thousands of bison across the Great Plains.

The crushed gravel road leading to their hives appeared to dead-end into the distant blue sky punctuated with perfect white clouds.

Some 4 million bees are in the 80 hives sitting on the hillside. Thousands danced midair above the hives, swooping and diving like high-flying acrobats. The air thrummed with the feverish beating of tiny wings.

North Dakota is a beekeeper’s paradise because of an abundance of wildflowers and canola crops, said Marin Tomulet.

The bees produce tons of rich, golden honey, worth thousands of dollars. Each hive brings about 100 pounds of honey that retails for $9 per pound.

After 18 years of beekeeping, Marin Tomulet said he has learned that the hives will thrive if given the proper care.

Varroa mites haven’t hurt his hives because he routinely treats for parasites, losing only 3 to 5 percent of his bees.

He also began switching between Amitraz and oxalic acid so that the mites wouldn’t develop immunity to one treatment.

Besides checking the bees every two weeks for pests, he takes care in the way he harvests the honey.

He and his wife pull hive frames filled with honey—some weighing a whopping 7 pounds—after applying a smelly substance containing butyric acid that repels the bees.

As the Tomulets remove the frames, they gently shake off any remaining bees before loading the honey onto an awaiting truck for processing.

Some producers simply blast the bees out of the boxes with air to save time.

While they will harvest most of the honey, Tomulet returns much of the wax comb to the bees because he knows how hard they work to produce it.

The Tomulets also leave enough honey in the hive to ensure the bees get enough nutrition. Otherwise, they will grow weak and more susceptible to disease.

They need that strength to survive the winter and the cross-country trips, he said.

As Prelipceanu, also from Romania, sees it, bees will take care of people if people take care of them.

“You have to have bees in order to have food. You have to have bees in order to have life—they are connected to each other,” he said.