By Michelle Plastrik

On Oct. 19, 2025, a brazen daytime robbery was committed at Paris’s Louvre while it was open to visitors. In under eight minutes, beginning around 9:30 a.m., thieves broke into the museum’s gilded Apollo Gallery, which houses precious royal objects. Two of the intruders entered through a window accessed via a cherry picker on a truck positioned by the Louvre’s Seine-facing façade. Two additional accomplices stayed on the street. Once inside, the criminals cracked two glass display cases containing French Crown Jewels and stole nine jewelry pieces of priceless historical value. After less than four minutes in the museum itself, they escaped back down via the truck’s lift. The whole crew sped away on motorized scooters, heading towards a nearby highway.

One item they took, the crown of Empress Eugénie, was dropped on the street and has been recovered. Unfortunately, it was crushed as it was being removed from the display case through a narrow opening and is damaged, but experts think it can be restored. Eight jewels remain missing, estimated to be worth around $102.1 million. As the clock ticks, it becomes less and less likely that the jewels will be recovered. Experts predict that the gems will be removed from their settings, the metal will be melted, many stones will be recut, and all valuables will be circulated into the international jewel market, never to be identifiable again.

The stolen jewels are an emerald necklace and earrings from a matching set owned by Empress Marie-Louise; a sapphire tiara, a necklace, and a single earring from the parure of Queen Marie-Amélie and Queen Hortense; and Empress Eugénie’s bow brooch, tiara, and reliquary brooch.

The Empress’s Wedding Set

Marie-Louise (1791–1847), daughter of the Holy Roman emperor and great-niece of Queen Marie-Antoinette, became the second wife of Emperor Napoleon in 1810. As empress, she needed impressive jewels to complement her new status. Many lavish sets, called parures, were ordered by Napoleon before and after the wedding from the French jeweler François-Régnault Nitot. (His firm became known later as Chaumet and remains a preeminent Parisian jewelry maison today.) Some were destined to be part of Marie-Louise’s personal collection, while others were designated as crown jewels.

One such personal parure, featuring exquisite emeralds, was offered by Napoleon to his bride on the occasion of their marriage. It consisted of a diadem, a necklace, a pair of earrings, and a comb. In 1814, Napoleon was exiled to Elba, and Marie-Louise left Paris for Vienna with these privately owned jewels, which she bequeathed later to various relatives. The emerald suite was left to her cousin Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany. His descendants held onto the jewels until 1953, at which time they sold them to Van Cleef & Arpels.

The jeweler removed the diadem’s emeralds and reset them, selling them to different individuals, dispersing their history. The diadem’s missing stones were replaced with turquoise, and the piece was acquired by American collector Marjorie Merriweather Post for the Smithsonian. It is on display in Washington’s National Museum of Natural History.

Marie Louise’s diadem with inserted turquoise gems on view at Washington’s Natural History Museum. Alvesgaspar/ CC BY-SA 4.0

Marie Louise’s diadem with inserted turquoise gems on view at Washington’s Natural History Museum. Alvesgaspar/ CC BY-SA 4.0The necklace, with 32 emeralds and 1,138 diamonds, and the earrings were preserved in their original state by Van Cleef & Arpels. They entered the collection of Baroness Elie de Rothschild before being acquired by the Louvre in 2004.

Stolen Sapphires

The stolen sapphire set, modified over centuries, has been worn by several royal women. The first definitively known owner was Queen Hortense of Holland (1783–1837), stepdaughter of Napoleon. Unsubstantiated legend has it that the sumptuous Ceylon sapphires were part of the collection of her mother, Empress Joséphine, and perhaps even go back to Marie-Antoinette.

The parure was bought from Hortense by the future King Louis-Philippe I of France for his Italian wife, Queen Marie-Amélie (1782–1866). In turn, she went on to gift grandchildren her jewels when they married. This set descended in the Orléans family until 1985, when the Louvre acquired the tiara, the necklace, the earrings, a large brooch, and two small brooches from Henri d’Orléans, count of Paris, for 5 million francs. The figure was less than they would have fetched on the open market as the count wanted them to remain in France. They were at the Louvre for 40 years, until the heist.

The tiara includes five main articulated elements, with each topped by a large sapphire. The piece in total has 24 sapphires and 1,083 diamonds.

The head ornament can be dismantled into brooches. This can be seen in a portrait of Marie-Amélie—the tiara pieces decorate the skirt of her gown.

The necklace, with eight sapphires supplemented by diamonds, is an example of great craftmanship. All of its links are articulated, meaning it was made with flexible parts that allow for movement; this feature gives a jewelry piece dynamism. The earrings have sapphire briolette pendants. Only one earring was taken in the robbery.

Eugénie’s Exquisite Tiara

The elegant Spanish-born Empress Eugénie (1826–1920) was a fashion trendsetter during the mid-19th century. As the wife of Emperor Napoleon III, who was the son of Queen Hortense and Napoleon I’s brother, Eugénie favored opulent dress and jewels. Shortly after her marriage, an official portrait of her was created by society painter Franz Xaver Winterhalter. The original was likely lost during an 1871 fire, but multiple copies of Winterhalter’s canvas survive.

The portrait shows the empress wearing a magnificent pearl and diamond tiara dated to 1853. This superb piece was commissioned by Napoleon III from court jeweler Alexandre-Gabriel Lemonnier as a wedding gift. Lemonnier used pearls from a parure made originally for Marie-Louise. The whole tiara consists of 212 natural pearls and 1,998 diamonds.

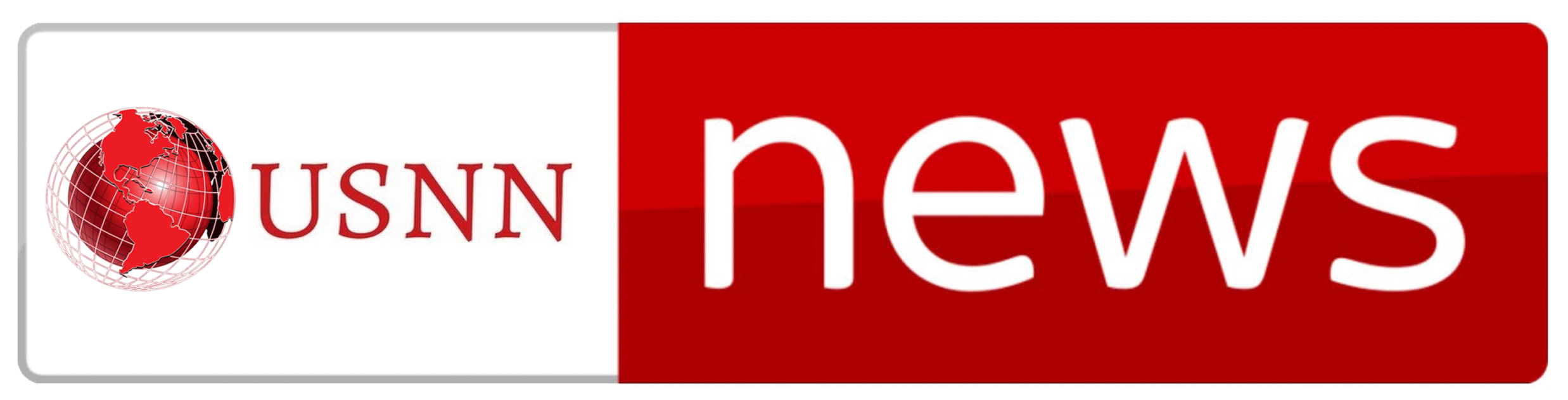

In 1870, Eugénie went into exile in England, and Napoleon III joined her the following year. As Marie-Louise had done, she took with her personally owned jewels when she left France. The tiara, considered part of the Crown Jewels, stayed behind. In 1887, a monumental jewelry auction of the country’s crown jewels was held at the Louvre. The French Third Republic, the government that had replaced Napoleon III’s Second French Empire, was wary of keeping these powerful symbols of royalty in their possession as they might inspire a monarchial restoration. Almost all of the jewels in the collection were sold, including Empress Eugénie’s tiara. In 1890, the German noble family Thurn und Taxis acquired the tiara. It passed through successive generations before being sold in 1992 at Sotheby’s for CHF 3,719,430 (approximately $420,000). It was purchased for display at the Louvre.

The recovered crown of Eugénie is featured in the Winterhalter portrait as well, where it is positioned on a pouf. The oil depiction of the gold, emerald, and diamond crown differs from the actual object; when Winterhalter painted the picture the crown had not yet been completed by Lemmonier. As a result, Winterhalter would have had to work from the jeweler’s working designs. The finished crown’s eight eagle-shaped arches are interspersed with diamond palmettes—both are imperial symbols. Topping the arches is a diamond globe surmounted by a cross.

Created for and exhibited in the Universal Exhibition of 1855, the Third Republic returned the crown to the empress in 1875. She bequeathed it to Princess Marie-Clothilde Napoléon, the daughter of her late son’s appointed heir. It has been part of the Louvre’s collection since 1988.

Bodice Bow Brooch

Eugénie’s bodice bow brooch by François Kramer is composed of 2,438 diamonds. Almost nine inches high, its size is astonishing. It was made in 1855 and later adapted in 1864. Of a virtuoso design, it is a sculptural bow with asymmetrical braids finished with tassels whose fringes are articulated. Five cascades of diamonds emanate from the bow; these are set “en pampille,” meaning they terminate in an icicle shape.

Sold in the infamous 1887 auction as the catalogue’s lot number five, the striking brooch was bought by a jeweler on behalf of the Gilded Age “queen” of New York high society, Caroline Astor, for 42,200 francs (over $8,000) at the time. In 1902, it was purchased by the Duke of Westminster for the marriage of his daughter to the seventh Earl Beauchamp. The wife of the eighth earl sold it to a New York gem dealer in 1980. When the dealer’s collection was to be sold in 2008 at Christie’s, the Louvre was determined to bring the brooch back to France. While the auction ended up being canceled, a private sale to the museum of the piece was negotiated for the sum of $10.7 million.

Royal Reliquary Brooch

Eugénie’s reliquary brooch was one of the few crown jewels not auctioned by the Third Republic. Instead, it joined the Louvre’s collection. Its name is a misnomer, as there is no space in the piece to house a relic. Scholars speculate that the brooch’s case may have been intended for this use. The brooch was made in 1855 by Alfred Bapst, whose family had been royal jewelers for generations. Beneath the rosette at the top of the brooch are two large diamonds, each reminiscent of a heart shape. These important stones can be traced to Cardinal Jules Mazarin. The chief minister of France, Mazarin assembled a legendary collection of 18 rare diamonds during the mid-17th century. Upon his death, he left them to King Louis XIV and the French Crown Jewels. The diamonds numbered 17 and 18 were used by the king as coat buttons and centuries later repurposed for Eugénie’s use.

In the 20th century, the Louvre, lamenting the loss of French history from the 1887 sale, began to buy back royal jewels. It is ironic that the eight stolen jewels were taken from a place that was meant specifically to safeguard them for the benefit of public display. The heartbreak caused by this theft is not merely over the loss of diamonds, sapphires, emeralds, and pearls, but the stories that the jewelry symbolizes. The are, or, maybe by now, were, living testaments to craftmanship, beauty, power, politics, and romance after all the players involved are gone. Emblematic of French heritage, their theft not only steals from the Louvre and the French people, but global citizens who love and value history.