By Kevin Stocklin

A few years ago, U.S. auto executives were hailing their conversion to electric cars and market analysts were predicting exponential growth in electric vehicle sales amid the inevitable extinction of the gas-powered engine.

Executives from General Motors (GM), Ford, Volkswagen, Mercedes, and Volvo pledged that their fleets would be 100 percent electric within a decade.

But, the reality has been quite different.

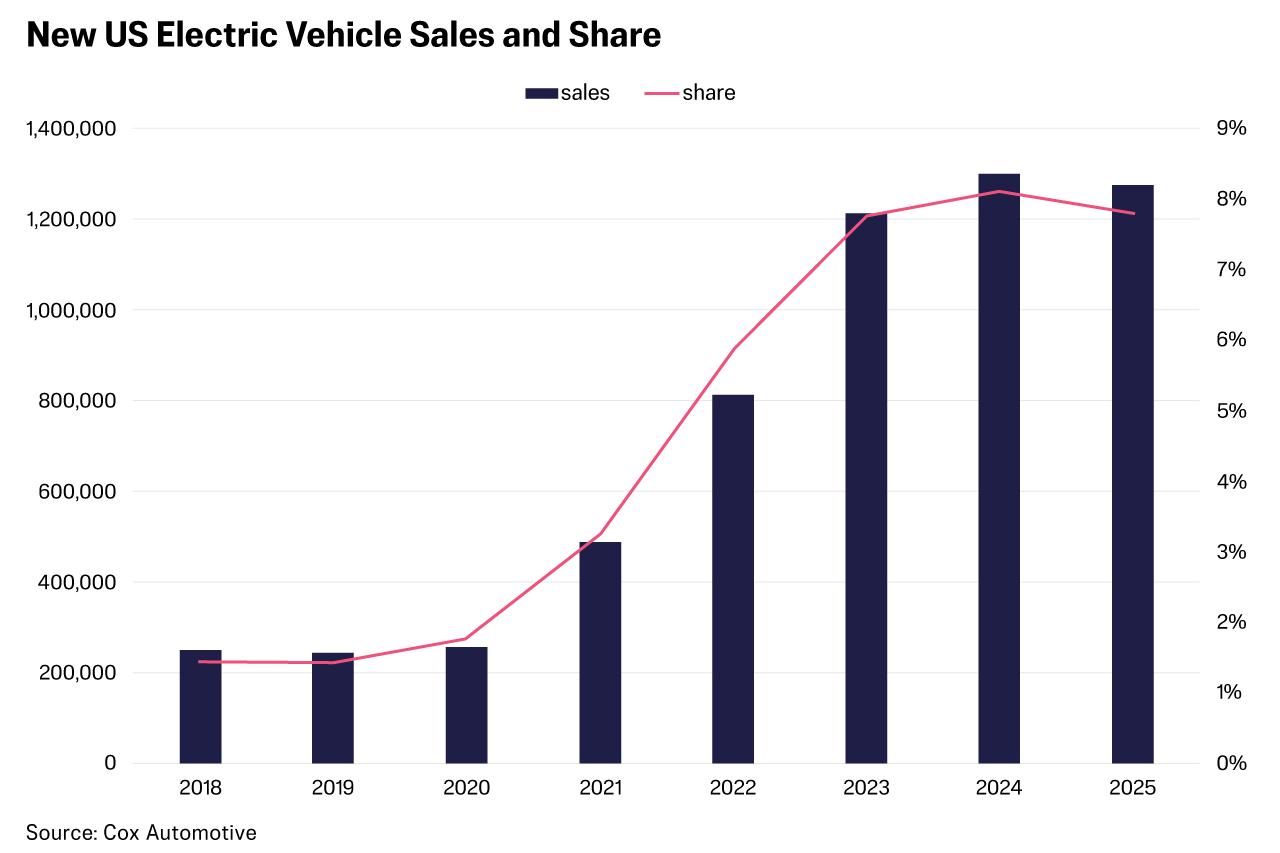

After President Donald Trump ended the $7,500 electric vehicle (EV) tax credit in September 2025, the sales growth of electric cars in America went into reverse, falling to 234,000 units in the fourth quarter of last year, down by 46 percent compared to the prior quarter, according to data from Cox Automotive.

The market share of EVs tumbled from 10.5 percent of all new cars sold in America in the third quarter of 2025 to 5.8 percent in the fourth quarter, according to Kelley Blue Book data.

“EVs will only grow very slowly from here on out due to a saturated market and lack of consumer demand,” energy analyst Robert Bryce told The Epoch Times.

Billions in EV Losses

American and European car manufacturers that had bet heavily on the EV transition are now licking their wounds.

Ford, GM, Mercedes-Benz, and Volkswagen collectively lost $114 billion on EV ventures between 2022 and 2025, according to a recent op-ed by Bryce. Adding a $26 billion write down on its EV line announced by Stellantis (formerly Chrysler) on Feb. 6, that total climbs to $140 billion.

In December 2025, Ford announced that it was canceling its flagship electric truck, the F-150 Lightning. Having lost $13 billion on its EV line since 2023, Ford announced a $19.5 billion write-down from EVs in the fourth quarter of 2025.

“The operating reality has changed, and we are redeploying capital into higher-return growth opportunities: Ford Pro, our market-leading trucks and vans, hybrids and high-margin opportunities like our new battery energy storage business,” Ford CEO Jim Farley said in a statement.

In January, GM announced a $6 billion write-down in its EV line, following its decision in October 2025 to take a $1.6 billion loss to scale back its EV investments. GM canceled contracts with electric vehicle battery suppliers, while Stellantis announced it would cut its entire plug-in EV lineup for 2026, though it still planned to introduce new long-range EV models that use gasoline to charge the car’s battery.

Tesla, once the leading EV producer, recently reported falling sales and profits, and CEO Elon Musk spoke of shifting the company’s focus toward robotics as Chinese manufacturer BYD overtook it in global sales of units sold.

Far from the inevitable demise of the internal combustion engine, other global auto companies’ ventures into electric vehicles now appear to be costly, highly dependent on government support, and vulnerable to fierce competition from China.

“The electric vehicle market in the United States was primarily created by government mandates and government subsidies,” Paul Mueller, economist with the American Institute for Economic Research, told The Epoch Times.

“Even Tesla would not have made it without significant government subsidies—over $3 billion—and regulatory credits bought from Tesla by other car producers—over $13 billion.”

Due to federal emissions regulations, which were tightened under the Biden administration, gas-powered vehicle producers who focused on the most profitable models such as trucks and SUVs, were compelled to buy emissions credits from EV manufacturers to offset their failure to meet fleet-wide Corporate Average Fuel Economy requirements. This additional multi-billion-dollar subsidy was also curtailed by the Trump administration.

Subsidies Drive Sales

While global EV sales have remained robust, increasing by 20 percent in 2025, the majority of those sales occurred in China, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, an EV research group. In other global markets, by contrast, demand for EVs was uneven, growing where subsidies and regulations incentivized buyers, falling where they did not.

Europe’s EV market, where buyer incentives remain in place, grew by 33 percent in 2025.

In the United States, by contrast, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, signed in July 2025, eliminated the $7,500 tax credit on new EVs, as well as the $4,000 credit for used models. In the absence of these incentives, Benchmark predicts that the U.S. market for electric cars and trucks will contract by up to one-third in 2026.

EVs have been attractive for affluent consumers who have shorter commutes and can charge them in their garages.

However, as a mainstream product, EVs have been hindered by high sticker prices, range anxiety, long charging times, diminished performance in cold weather, and—as evidenced from power outages during recent snowstorms—an occasional inability to use them during crises.

Another concern for buyers is that EVs don’t hold their value well, according to iSeeCars, an automotive research company.

EVs lose 58.8 percent of their value in the first five years after purchase, compared with the industry average for all vehicles of 45.6 percent, the report states. Trucks and hybrids fared the best, both losing about 40 percent of their value over five years.

Part of this is likely due to a comparatively poor service record for EVs, despite the fact that they were marketed as requiring less maintenance than gas-powered cars. A December 2025 report by Consumer Reports stated that EVs have about 80 percent more service problems on average than gas-powered cars.

On the other hand, hybrids, which combine a gas engine and electric battery, have 15 percent fewer problems on average than gas-only cars. Hybrids have been in production longer than EVs, and this likely has improved the reliability of more recent hybrid models and provides hope that EVs will likewise become more reliable in time.

China Advantage

Critics of Western automakers’ retreat from EV production say they are surrendering a critical advantage to China. In response, EV critics argue that Western carmakers could bankrupt themselves by betting too heavily on electrics for two reasons.

The first is that abandoning gas-powered vehicles means giving up much of the engineering expertise and brand reputation that carmakers have developed over decades. Second, China’s stranglehold on the raw materials for batteries, and its lower production costs, means China will likely retain a substantial competitive advantage in the EV market.

China’s price advantage is due to a number of factors, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

“Over 70 percent of all EV batteries ever manufactured were produced in China, creating extensive manufacturing know-how,” the IEA states. “This has supported the rise of giant manufacturers such as CATL and BYD, which have centralized expertise in the battery sector and driven innovation.”

Chinese control of raw materials and supply chains has often limited Western carmakers’ role to little more than downstream assembly.

In addition, the report states, “Fierce domestic competition has shaped the Chinese battery market, which is home to almost 100 producers. To maintain or gain market share, these firms have been cutting their profit margins to sell batteries at lower prices.”

BYD has displaced Tesla in 2025 as the world’s largest seller by volume, and in some markets, BYD’s EVs sell for 30 percent less than other global brands, and have longer ranges and offer higher-quality interiors. Chinese automakers have already captured a 10 percent market share in Europe.

Rethinking Regulations

Despite this, regulations in Europe, and in many Democratic-led U.S. states, have attempted to force carmakers to abandon gas-powered cars and trucks. The EU has banned the sale of new cars and trucks that run on gasoline or diesel fuel, starting in 2035.

U.S. states that have banned or have plans to ban the sale of gas-powered cars and trucks by 2035 include California, Washington, Oregon, New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Delaware, and Maryland.

However, these plans may not survive, particularly if automakers are unwilling to produce enough EVs to satisfy the compulsory demand for them. Already, fearing the loss of an auto industry that represents 7 percent of Europe’s GDP and employs 13 million workers, the EU has been rethinking its looming bans on gas-powered cars.

In December 2025, the EU reduced its zero-emission requirement for new cars from 100 percent to 90 percent. The European carmakers association, ACEA, had argued that the 100 percent goal is unrealistic given the relatively weak demand for electric cars.